Interpretive Trail Signs

The trails at Sunset Beach have a series of interpretive signs with information about Lake Diefenbaker, the Sunset Beach site, local plants, animals, and more. Each sign also has a QR code that you can scan to bring you to the corresponding topic on this page to learn more information.

Macroinvertebrates

Macroinvertebrates are organisms without backbones that you can see without using a microscope or magnifying glass. They are great indicators of biological conditions in waterbodies.

Some of the macroinvertebrates you may find living in Lake Diefenbaker include:

Backswimmer (1): named for their habit of swimming upside-down, with their back facing downward. They are predators that use their long hind legs for propulsion and piercing mouths to prey on other aquatic organisms, including mosquito larvae.

Whirligig beetle (2): water beetles that are known for their distinct behavior of swimming in fast, erratic circles on the water’s surface. They are highly social, often forming large groups, especially in sunny areas. They have divided compound eyes that allow them to see above and below the waterline simultaneously.

Caddisfly Larva (3): predominantly feed on algae, plant matter, and organic debris. They are great indicators of water quality, as they are sensitive to pollution. They construct protective cases using silk, pebbles, sand, and plant debris.

Water Boatman (4): have flattened bodies adapted for swimming and possess oar-like hind legs that they use for propulsion. They are omnivorous, feeding on algae, detritus (dead particulate organic material), and small invertebrates.

Leech (5): feed on the blood of other animals. They have cylindrical bodies and suckers at both ends which they use for locomotion and attachment to hosts.

Dragonfly Larva (6): can spend up to 5 years living underwater before becoming adult dragonflies. They are voracious predators, using their extendable jaws to capture prey such as small fish, tadpoles, and other aquatic invertebrates.

Snail (7): gastropod mollusks characterized by their coiled shells. Most snails are herbivores and feed on algae, plants and decaying organic matter. They play an important role in nutrient cycling and are often preyed on by other animals.

Leopard Frog (11) & Tadpole (8): Leopard frogs start as eggs from which tadpoles hatch. The tadpoles feed on algae and plant matter. As they grow, they develop legs and lungs and become medium sized frogs, named for the distinctive spots on their backs. They are opportunistic feeders, using their long, lightning fast tongues to catch insects, fish, tadpoles, and crustaceans.

Damselfly Larva (9): closely related to dragonflies, but smaller with slimmer bodies. Fully grown damselflies come in a variety of colors including metallic blues, greens, and reds. They are voracious predators and use their highly specialized legs to catch and immobilize prey. They are agile fliers and can maneuver quickly.

Water Mite (10): tiny arachnids that often attach to plants or animals. They are parasitic and predatory creatures.

Discover What's Living in Lake Diefenbaker by Pond Dipping

How to Pond Dip:

1. The main items required for pond dipping are a long poled net with mesh material & a white tray to observe your specimens. A magnifying glass and pond life guide book will also be helpful.

2. Scoop some of the water into your tray to create a mini environment for your critters to swim in.

3. Stand on the edge of the water near vegetation. Docks are great places to stand.

4. Dip your net into the water slowly. If you go too quickly, you might scare the creatures away. Use a figure eight motion to swirl your net slowly a few times in the water.

5. Pull the net from the water and gently dump it into your tray.

6. You can use a stick to gently spread any plants and slime around to see any hidden creatures.

7. Use a magnifying glass to get a closer look and use a guide book, or your cell phone to identify the specimen.

8. When you are done, dump the tray contents back into the water.

9. Rinse out your net and tray and make sure to wash your hands with hot water and soap.

Other interesting links:

Wascana Centre Guide to Pond Dipping

Wascana Centre Macroinvertebrate Identification Key

Wascana Centre Macroinvertebrate Pond Dipping Key

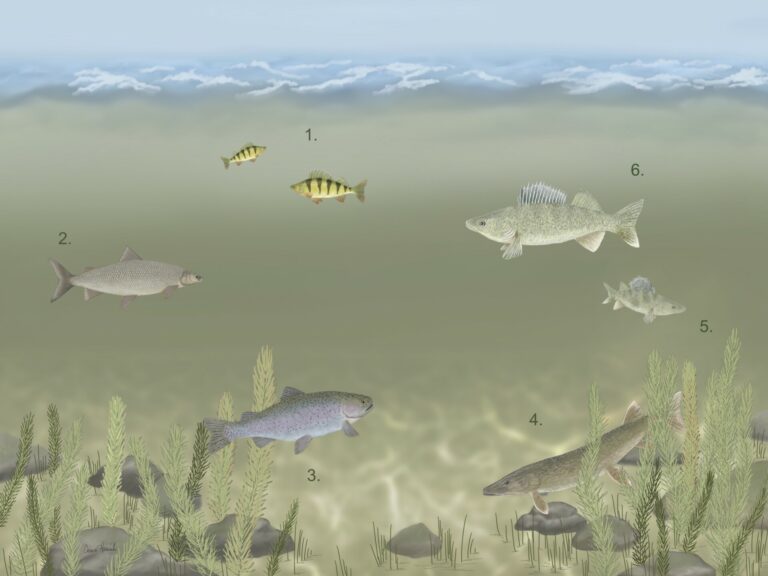

Fish

Lake Diefenbaker is home to 26 native and stocked species of fish.

The most common fish species you will find in Lake Diefenbaker include:

Yellow Perch (1): characterized by their bright yellow/golden coloration with vertical stripes. They are popular with anglers for their abundance, accessibility, and delicious, flaky flesh.

Lake Whitefish (2): characterized by their silvery coloration, streamlined body, and small upturned mouth. They are prized for their delicate flavor and firm flesh.

Rainbow Trout (3): known for their strikingly beautiful coloration, including a pink stripe along their sides, greenish-blue back, and silver belly. They are popular for their fighting ability and delicious flesh. The world record rainbow trout was caught on Lake Diefenbaker by Sean Konrad on September 5, 2009. It weighed 48 lbs. 0 oz, had a length of 42″ and a girth of 32″.

Northern Pike (4): large predatory fish characterized by their elongated body, sharp teeth, and olive-green coloration, with lighter spots and stripes. They are apex predators that prey on fish, frogs, and small mammals. They are popular for sport fishing.

Sauger (5): similar in appearance to the walleye, but distinguished by its smaller size, darker color, and irregularly spaced spots on its dorsal fin. They are also prized by anglers for their taste.

Walleye (6): named for its distinctive pearlescent eye, which reflects light and enhances its vision in low light conditions. They are highly prized by anglers for their tasty, flaky white flesh. There are several walleye fishing tournaments on Lake Diefenbaker every year.

Lake Trout: known for their distinctively colored spots and forked tail. Sought after by anglers for their large size, aggressive behavior, and delicious flesh.

Burbot: nocturnal predators, often found in the deep, cold waters where they feed on fish, crustaceans, and other small aquatic organisms. They are known for their eel-like appearance, mottled brown coloration, and distinctive barbels around their mouth. The world record burbot was caught on Lake Diefenbaker by Sean Konrad on March 27, 2010. It weighed 25 lbs. 2 oz and had a length of 41″.

Goldeye: named for its large, reflective golden eyes. They are known for their silvery color, deep body, and upturned mouth.

Check out these links for more info about fish in the area:

Lake Diefenbaker Tourism Fishing

Fish Species of Saskatchewan

Birds

The Lake Diefenbaker area is home to a wide variety of birds that can be found around the shoreline as well as in their native shrub habitat.

Some of the more common birds in the area include:

Eastern Kingbird (1): similar in appearance to the Western Kingbird, but have a darker head, white tipped tail feathers, and less prominent white throat patch. They are known for their aggressive behavior, often driving away larger birds such as crows and hawks from their territory.

Kildeer (2): a medium sized plover known for their brown back, white underparts, and two black bands across their breast. They are named for their loud, piercing “kill-dee” call, which they use to communicate with each other and warn of threats.

Western Kingbird (3): a medium sized passerine bird known for their bold black and white plumage, long pointed bills, and distinctive white outer tail feathers. They are often seen perched on fence posts, trees, or wires, where they hunt for flying insects.

Franklin’s Gull (4): a small, migratory gull. They have a black hood, white eye crescents, and pinkish-grey underparts.

Willet (5): a large shorebird with distinctive black and white striped pattern on their wings and a long straight bill. They probe the sands for crustaceans, mollusks, and other invertebrates.

Red-winged Blackbird (6): a common songbird. Males have glossy black plumage and distinctive red and yellow shoulder patches. They are highly territorial during breeding season. They feed on a variety of foods including seeds, insects, fruits, and small vertebrates.

Loggerhead Shrike: a threatened bird in the Saskatchewan prairies. It does not have talons like other birds of prey. It uses its hooked beak to catch its prey and impales it on barbed wire fences or thorny shrubs like the thorny buffaloberry. Keep a watch out for any impaled critters on your walk and report any sightings to Nature Saskatchewan, who monitor their population.

Canada Goose: known for their distinctive black heads and necks, white cheek patches, and honking calls during migration and flight. They are migratory birds, breeding in northern regions during the summer and migrating south to warmer areas over the winter.

Crow: highly adaptable, intelligent and social birds. Often seen in family groups or large flocks where they communicate with a variety of vocalizations. They feed on a wide range of foods including seeds, fruits, insects, and small mammals.

Yellow-headed Blackbird: named for their bright yellow head and throat contrasting with their black body and wings. They are highly social and often form large breeding colonies.

Mallard Duck: one of the most familiar and widespread duck species. They have bright yellow bills, the males have a distinctive green head, and the females have a brown mottled plumage. Lake Diefenbaker has one of the largest duck populations in North America.

Here are some links to help you identify birds by their looks and sounds:

eBird

Merlin Bird ID– Download the app to identify birds you see and hear

All About Birds

iNaturalist

Piping Plover

Sunset Beach is located in the East Lake Diefenbaker Important Bird and Biodiversity Area. It was designated because the lake supports the largest populations of Piping Plovers in Saskatchewan. Piping Plovers are an endangered shorebird due to habitat loss, disturbance, and predation.

They are small, sparrow-sized birds with pale sandy-brown to white plumage on their backs and wings. They have a white belly and chest with a single black breast band that extends across their neck. Their legs are pale orange, and their bills are orange with a black tip.

Piping Plovers nest by scraping out a shallow bowl in the sand and lining it with pebbles. The young are roughly the size of a cotton ball.

If they spot a predator near their nest, they try to lead it away by pretending to have a broken wing.

Piping Plovers eat freshwater invertebrates. They run, stop, and peck into the sand.

Learn more about the piping plover at these links:

Important Bird Areas Canada (IBACanada)

Nature Saskatchewan

All About Birds

Plants

There is an abundance of beautiful plant life around Lake Diefenbaker. Some plants bloom as early as April and others as late as September. Can you spot these species?

(* bloom times)

Wild Bergamot (1) (*June to September): Also known as Bee Balm, this is a very fragrant native prairie plant. Leaves can be harvested to make a mint like tea. Wild Bergamot flowers attract pollinators to the area such as butterflies and hummingbirds.

Common Yarrow (2) (*May to July): Yarrow is an ancient herb recognized for its medicinal uses long ago. Fossils of this plant have been found in Neanderthal burial caves more than 60,000 years ago. The Cree used yarrow tea to sooth earaches and relieve colds, diarrhea, and fever. Chewing the leaves can relieve a toothache. Crushed yarrow on bleeding wounds can stimulate clotting and can soothe chest and muscle pains.

Pasture Sage (3) (*August): Sage is a sacred medicine in Indigenous culture. Smudge is a form of ceremony that involves burning sage and bringing the smoke over your body. It is a traditional way of cleaning the four parts of your self- mind, body, emotions, and spirit. It is used to fill a person or space with good energy.

Prickly Rose (4) (*May to July): The fruit of the rose bush is called a rose hip. Three rose hips contain the same amount of vitamin C as a whole orange. They also contain Vitamin A, B, E & K. The inside of the rose hip contains tiny seeds covered in silver-like hairs. The tiny seeds need to be removed before ingesting, as they can cause irritation in the digestive tract. The hips can be boiled to make tea, jam, jelly or syrup and made into wine. Rose petals can also be eaten, and make a great addition to a salad. The Cree boiled roots to make a tea to treat coughs. They also used the hips to make jewelry and used hollowed hips to make toy pipes.

Blue Grama Grass (5) (*July to August): Also known as Grandma’s Eyelashes. The seed head of the Blue Grama Glass resembles an eyelash. This species blooms late in the season and is draught tolerant. It’s an important foraging species for producers in draught years.

Creeping Juniper (6) (*June): The Creeping Juniper is characterized by its spreading growth, as its branches creep along the ground. The foliage consists of needle like leaves, typically green to blue-green in color. Some Indigenous tribes used the juniper berries as a food source and for making tea. They also used the branches and leaves for basketry, shelter construction, or a ceremonial smudge. The dense foliage provides cover and nesting sites for birds, small mammals, and insects. Its essential oils are used in aromatherapy and fragrances.

Prickly Pear Cactus (7) (*June): Fruits of this plant are cylindrical, brownish, and have short, stout spines. The flowers can be yellow, orange, pink, or red. The oval green pads and the fruits can be eaten once the spines have been removed. They are a source of water.

Chokecherry (8) (*May to June): The Cree made medicinal teas from dried Chokecherry bark to treat colds, coughs, and pneumonia. The berries were mixed with animal grease and sometimes fish eggs to make pemmican. Chokecherry wood is very hard and does not burn easily. Sticks were often used to carry hot items such as heated rocks for sweat lodges and hot coals for smudges. The hard wood was often used to make digging sticks, tent poles, back rests, and household tools.

Pincushion Cactus (9) (*June): With a lot of patience, these cacti are edible once the spines have been removed. They are characterized by dense clusters of cylindrical or spherical stems covered in spines. They also produce small colorful flowers in white, pink, or yellow.

Thorny Buffaloberry (10) (*April): The red or orange berries of the Buffaloberry shrub are edible. The tart berries can be harvested and made into jams or jellies. It is valued for its ornamental and wildlife value, as it provides habitat and food for birds, small mammals, and insects.

Here are some links to learn more about these and other plants native to Saskatchewan:

Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Native Plant Photos

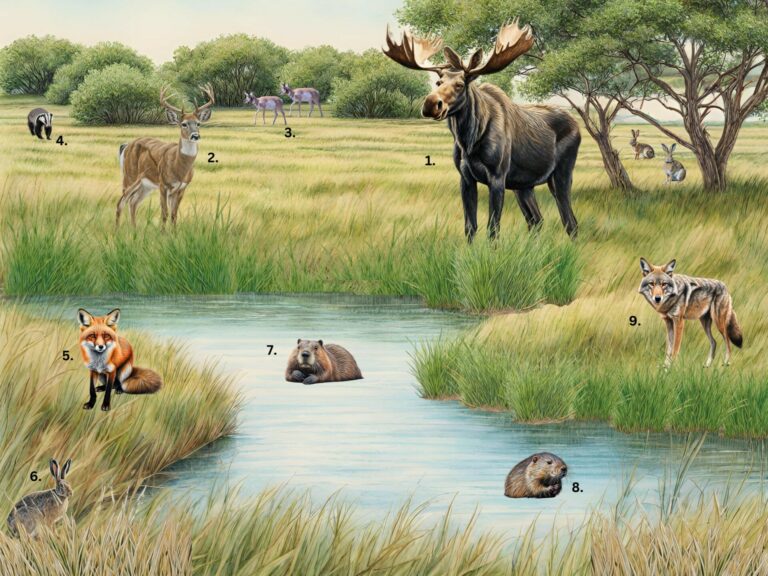

Wildlife

There are many different species of animals that make the Lake Diefenbaker area their home. Some of them you can see on a regular basis and others are stealthier and harder to find.

Have you seen these animals around Sunset Beach:

Moose (1): characterized by their massive size, long legs, humped shoulders, and distinctive broad palmate antlers. Moose are solitary animals for most of the year, except for rutting season. They are primarily herbivores and are excellent swimmers.

White-tailed Deer (2): known for their distinctive white underside of their tail, which they raise as a warning signal when alarmed. They are smaller, have shorter legs, and a rounder body than mule deer. Their antlers are usually smaller and less branched, with a single main beam with smaller tines. They play a crucial role in maintaining the ecosystem balance.

Pronghorn (3): known also as pronghorn antelope, have a tan or reddish brown coat with white underside and white patches on the neck and rump. They have large, forward curving horns with a distinctive prong, which gives them their name. They are the fastest land mammals in North America and one of the fastest in the world, able to sustain speeds up to 55 miles per hour for several miles.

Badger (4): known for their stout bodies, short legs, and distinctive facial markings, including a white stripe from their nose to the back of their head. They are skilled diggers and excavate elaborate burrow systems that are used for shelter, nesting, and storing food. They are opportunistic hunters, feeding on small mammals, insects, reptiles, and bird eggs.

Red Fox (5): distinguished by their reddish-orange fur, white-tipped tail, and pointed ears. Foxes are solitary animals except during breeding season when they form monogamous pairs. They are omnivores, feeding on small mammals, birds, insects, fruits, and carrion.

Jackrabbit (6): characterized by their long hind legs, long ears, and black tipped tails. Jackrabbits are actually hares. Their fur color can range from sandy brown to gray to reddish-brown.

Beaver (7): known for their dam building behavior and engineering prowess. They use branches, mud, and vegetation to create ponds that provide habitat for themselves and other wildlife. Beavers feed on tree bark, leaves, aquatic plants and shrubs.

Muskrat (8): semi-aquatic rodents with webbed hind feet and waterproof fur. Muskrats feed on aquatic plants, cattails, and sedges, which they gather and store in their lodges for winter.

Coyote (9): known for their adaptability and cunning hunting techniques. Coyotes often hunt in pairs or small family groups. They are opportunistic feeders, preying on small mammals, birds, insects, and carrion. They help regulate prey populations and serve as scavengers.

Porcupine: large rodents with spiny quills that cover their body and act as a defense mechanism against predators. They are solitary animals and primarily nocturnal, resting in trees or dens during the day.

Cottontail Rabbit: named for their distinctive fluffy white tail. They feed on a variety of grasses and woody plants. They rely on camouflage and agility to avoid predation from foxes, coyotes, hawks, and owls.

Mule Deer: named for their large ears, which resemble those of a mule. They are larger, have longer legs, and a larger elongated body compared to white-tailed deer. They have a white rump and tail with a black tip at the end. Their antlers are typically larger and more branched with multiple points on each antler, with distinctive “forked” appearance.

Skunk: known for their distinctive white stripes that run down their backs and tails as well as their potent defensive spray. Striped skunks are solitary and mostly active at night. They forage for food and patrol their territory.

Raccoon: recognizable for their distinctive facial masks, ringed tail, and dexterous front paws, that are used for manipulating objects and food. They use their keen senses of smell and touch to locate prey and are often seen foraging for food at night.

Learn about more animals that you can find in Saskatchewan:

iNaturalist Saskatchewan Mammals

Animalia Animals of Saskatchewan

Land Acknowledgement

Sunset Beach is located near the boundary between Treaty 4 Territory and Treaty 6 Territory, and all of the people here are beneficiaries of these treaties. Treaty 4 encompasses the lands of the Cree, Saulteaux, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota, and the homeland of the Métis Nation. Treaty 6 encompasses the lands of the Cree, Saulteaux, Dakota, and Nakota, and the homeland of the Métis Nation. This acknowledgement reaffirms our relationship with one another, and we are committed to moving forward in partnership with Indigenous Nations in the spirit of reconciliation and collaboration.

Sunset Beach "Reconcili-ACTION" Plan

Sunset Beach is committed to the following actions around Truth and Reconciliation:

1. Education:

Sunset Beach is committed to playing their part on the 94 Calls to Action. Action 92 iii Business and Reconciliation states: Provide education for management and staff on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal-Crown relations. This will require skills based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism.

All staff at Sunset Beach have completed the 4 Seasons of Reconciliation education course offered by First Nations University of Canada. We also attended a Heritage Webinar presented by the Government of Saskatchewan about the Buffalo Child Stone. Some staff members also attended Cultural Humility Training presented by the Aboriginal Friendship Centres of Saskatchewan. We will continue to seek opportunities to learn about Indigenous ways of knowing.

Sunset Beach recognizes and promotes important dates such as National Indigenous History Month (June), National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day, and other Indigenous led events and initiatives.

2. Collaboration:

Sunset Beach is committed to working with local Indigenous organizations, community builders, artists, advocates, and other Indigenous Elders and knowledge holders.

Sunset Beach is building relationships with the following local Indigenous led organizations:

Honey Willow nehiyaw Studios

Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Lean Man First Nation

Whitecap Dakota First Nation

3. Recognition:

Sunset Beach recognizes Treaty rights and adheres to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Indigenous History of the Area

The presence of Indigenous peoples on the Canadian Prairies dates back to prehistoric times. Archaeological evidence suggests that they have occupied what is now Saskatchewan for at least 10,000 years. The Lake Diefenbaker area was significant for various Indigenous communities, including the Cree, Saulteaux, Dakota, Nakota Sioux, and Métis peoples. These communities relied on the abundant resources provided by the lake and its surrounding lands for sustenance, trade, and cultural practices.

Each of these Indigenous peoples had their own distinct languages, cultures, and territories.

Cree (Nehiyawak): The Cree are one of the largest Indigenous groups in Canada, divided into numerous bands and subgroups, each with its own territory and dialects of the Cree language. Cree communities were found along major waterways such as the Saskatchewan River, Churchill River, and North Saskatchewan River, as well as in the boreal forest and taiga regions. They practiced hunting, fishing, trapping, and gathering. Cree traditions include powwows, sun dances, storytelling, sweat lodge ceremonies, Medicine Wheel teachings, birch bark canoe building, beadwork, quillwork, and berry picking.

Nakota Sioux (Assiniboine): The Nakota Sioux historically lived in the southern portions of Saskatchewan, particularly along the South Saskatchewan River and Battle River, as well as the Cypress Hills area. They are closely related to the Dakota and Lakota, and speak Nakota, a Siouan language. The Nakota traditionally hunted buffalo and other game, and engaged in trade with neighboring Indigenous groups. Nakota traditions include distinctive artwork, regalia, ceremonies, buffalo hunts, bison jumping, sun dances, dreamcatchers, and storytelling.

Dakota (Sisseton, Wahpeton): The Dakota are a group of Sioux peoples who historically inhabited the plains, in parts of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, North Dakota, and South Dakota. They are closely related to the Lakota and Nakota peoples and speak Dakota, a Siouan language. The Dakota were traditionally buffalo hunters and practiced a semi-nomadic lifestyle. They have a rich oral tradition, with stories, legends, and songs passed down through generations. Dakota traditions include sun dances, vision quests, pipe ceremonies, buffalo dances, star knowledge, and winter counts.

Saulteaux (Anishinaabe): The Saulteaux were closely related to the Ojibwe peoples of the Great Lakes region and speak a dialect of the Anishinaabemowin language. They inhabited the eastern and southeastern portions of Saskatchewan, along the Saskatchewan River and Qu’Appelle River. The Saulteaux practiced hunting, fishing, gathering, and agriculture. Saulteaux stories often feature Nanabozho, a trickster figure and cultural hero, who is said to have shaped the land and taught the Saulteaux people important lessons about life and survival. Saulteaux traditions include wild rice harvesting, birch bark canoe making, pipe ceremonies, sweetgrass braiding, berry festivals, storytelling, and drumming circles.

Métis Nation: The Métis Nation is a distinct Indigenous group with mixed European and Indigenous ancestry. During the fur trade era, they served as interpreters, guides, and traders. Métis communities were found along the South Saskatchewan River, North Saskatchewan River, Red River, parts of Manitoba, and settlements and trading posts established by fur traders, missionaries, and settlers. Métis traditions include the Red River Jig, Michif Language, fiddle music, Red River cart races, and bison hunts.

Blackfoot: The Siksika was one of four tribes in the Blackfoot Confederacy. They each had their own territory, leadership and traditions, but united for defense and shared governance. While the traditional territories of the confederacy primarily lie in Alberta and Montana, the Siksika ventured into southern Saskatchewan for hunting and trade. The name “Blackfoot” came from the dark colored moccasins they wore, which distinguished them from other tribes. Women played important roles in decision making and governance, and their society was matrilineal (meaning descendants were traced through the mother’s lineage). The Blackfoot were semi-nomadic, following the movements of the buffalo herds for hunting, gathering, and trading. Traditions of the Blackfoot include buffalo culture, tipi living, sun dances, medicine pip ceremonies, sweat lodge ceremonies, vision quests, singing and drumming. They have a legacy as buffalo hunters, warriors, and guardians of the plains.

These Indigenous groups historically interacted with each other in various ways including trade, warfare, alliances, cultural exchange, and intermarriage. Their territories were dynamic and interconnected. Many of the Plains Indigenous peoples were nomadic, and followed the buffalo herds. They traveled in family groups and used tipis for portable dwellings. The buffalo provided meat for food, hides for clothing and shelter, and bones for tools and weapons. Buffalo hunts involved skilled hunters, strategic planning, and ceremonial rituals to honor the spirit of the buffalo.

The South Saskatchewan River served as a natural boundary, transportation route, and meeting place, facilitating trade networks, alliances, and social interaction. It was a crossroads that connected the plains to the boreal forest, Rocky Mountains, and the Hudson Bay. The river provided a vital source of fresh water and supported daily needs for drinking, cooking, bathing, and irrigation. Settlements and campsites were often established along the riverbanks. The river was rich in fish, waterfowl, and plants that supported their livelihoods. Ceremonies and rituals were often conducted along the shores to honor the land, the water, and the spirit within. Indigenous peoples had a deep respect for the land and its resources. They used controlled burning, crop rotation, and other methods to maintain healthy ecosystems. Their beliefs centralized a closeness to the land and the environment.

The first European explorer believed to reach what is now Saskatchewan was Henry Kelsey in 1690. Many more explorers came over the 18th and 19th centuries. The introduction of explorers and fur traders brought new experiences and opportunities, as well as new struggles and changes. They were able to exchange furs, hides, pemmican and goods for firearms, metal tools, cloths, and beads. There were also opportunities for trade agreements and access to resources. The introduction of horses and guns allowed the Blackfoot to expand their territory and become one of the dominant tribes in the region. Alliances the Blackfoot had with the Nakota and Cree broke down and they became rivals. The Nakota and Cree traded with the Saulteaux and formed what became known as the Iron Alliance. The Métis played an important role with the North West Company, which threatened the Hudson’s Bay Company’s control over the trade industry. Eventually, these companies were forced to merge in 1821. Buffalo herds declined due to overhunting, disease, and habitat loss, which was devastating for the Plains Indigenous peoples. Settlers also brought new diseases such as smallpox, measles, and tuberculosis, which ravaged Indigenous populations with little immunity.

The decline of the fur trade, agricultural expansion, and construction of railways and settlements led to the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their traditional territories. Treaties were negotiated to establish agreements regarding land rights, resource sharing, and other provisions in exchange for cession of territory and cooperation. However, the terms of the treaties were often misunderstood or misrepresented, which lead to ongoing disputes. Indigenous leaders from different nations often came together to discuss the terms and advocate for their communities’ interests, which led to some alliances and agreements between the nations.

Competition for access to hunting territories, control over trade routes, and disputes over payment and fair treatment could lead to violence and conflict. Some tribes were wiped out or forced out of the region. The North West Mounted Police were established in 1873 and they were tasked with maintaining law and order in the Canadian territories. They enforced government policies such as the Indian Act of 1876, which was often met with tensions from Indigenous communities who resisted efforts to assimilate and control their way of life.

Many Indigenous peoples were relocated to reserves, which they believed would be permanent homelands for their descendants, but completely changed their ways of life. Their movements outside of the reserve were controlled. Residential schools were introduced during this time as well, where Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families, with the goal of assimilating them into Euro-Canadian culture. Instead, it often led to physical, emotional, and cultural abuse resulting in intergenerational trauma. With the decline of the buffalo resources, they became increasingly forced to rely on government rations, farming, and wage labor to survive.

Despite these challenges, the Plains Indigenous peoples demonstrated resilience and resistance. Some communities engaged in armed resistance, including the North West Resistance of 1885. Others pursued legal and political avenues to assert their rights, advocate for land claims, and preserve their cultures and identities.

Some prominent historical Indigenous figures in the Saskatchewan area include: Poundmaker (Pîhtokahanapiwiyin), a revered Cree leader known for his wisdom and efforts to seek peace and who played a significant role in negotiations between the Cree and the Canadian government during the Nort West Resistance; Big Bear (Mistahi-maskwa), a prominent Cree Chief who resisted the encroachment of settlers and played a key role in events leading up to the North West Resistance; Louis Riel, a Métis leader and political activist who fought for Métis rights and played a central role in the Red River and North West Rebellions; Gabriel Dumont, a Métis leader who organized and led forces against the Canadian government troops during the North West Resistance; Crowfoot (Isapo-muxila), a Siksika Blackfoot Chief known for his diplomacy and efforts to negotiate treaties and protect the Blackfoot way of life; Mistawasis, a Plains Cree Chief who played a role in negotiating Treaty 6 and advocating for his peoples interests; Ahtahkakoop (Atahkakohp), Chief of the House Cree who, along with his friend Mistawasis, signed Treaty 6 and led his people through transition into the new way of life; Fine Day (Kamiokisihkew), a Plains Cree Chief known for his efforts to maintain peace and cooperation between Indigenous peoples and settlers; White Cap (Wapaha Ska), a Plains Cree Chief who also played a role in negotiating treaties; Wandering Spirit (Kapamahchakwew), a Plains Cree leader who was involved in the Battle of Cut Knife and participated in events of the North West Resistance; and Piapot, a Cree Chief known for his efforts to resist colonial encroachment and his involvement in negotiations with the Canadian government.

To learn more about the history of Indigenous Peoples in Saskatchewan, we encourage you to review these links:

Indigenous Peoples of Saskatchewan

First Nations, Metis, and Northern Citizens

Indigenous History- Submitted by Wyatt Brown from the Whitecap Dakota Nation

The history of First Nations peoples in North America/Canada is rich, diverse, and stretches back thousands of years. Before the arrival of European colonizers, Indigenous peoples inhabited the land now known as North America/Canada for thousands of years. They developed sophisticated cultures, languages, and social structures, with diverse societies ranging from nomadic hunter-gatherer groups to sedentary agricultural communities. First Nations peoples had deep spiritual connections to the land and practiced a variety of traditional beliefs and ceremonies. As European colonization expanded, First Nations peoples faced increasing pressure on their lands and resources. Treaties were negotiated between Indigenous nations and colonial governments, often resulting in the cession of land in exchange for promises of protection, education, and other rights. However, many treaties were later broken or disregarded by the Canadian and U.S. governments, leading to land dispossession, forced relocations, and the erosion of Indigenous rights. In recent decades, there has been a growing acknowledgment of Indigenous land rights and the need for meaningful reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Initiatives such as land acknowledgments, land claims settlements, and co-management agreements aim to address historical injustices, promote Indigenous self-governance, and support the sustainable management of First Nations lands.

Indigenous peoples continue to face a range of challenges and opportunities around the world. Many Indigenous communities are actively working to revitalize their languages, cultures, and traditions. This includes efforts to preserve traditional knowledge, promote Indigenous arts and crafts, and reclaim cultural practices that were suppressed or lost due to colonization.

-Submitted by Wyatt Brown. originally from Canupawakpa Dakota Nation in Manitoba, currently resides in Whitecap Dakota Nation in Saskatchewan. Wyatt is a powwow dancer and interpreter. He works at Dakota Dunes Resort as an Adventures Assistant Manager, and was recently awarded the ITAC Outstanding Staff Persons Award.

Indigenous Games

Traditional Indigenous games have been played by Indigenous people for generations. These games are not only fun, but also teach important skills required to live off the land, such as hand-eye coordination and stealth, while increasing strength, lung capacity, and endurance.

Here are a couple of Indigenous games to try:

Run & Scream

- Find an open flat area.

- Line up horizontally.

- Count to three in Cree: “pêyak” (pay-yahk), “nîso” (nee- soo), “nîsto” (nee- stoo).

- Take a deep breath in and say “mâcihta” (maw-chee-tuh).

- Start running and scream at the top of your lungs.

- Once you have no more air left in your lungs, stop running.

- The person who runs the farthest in one breath, wins.

Rock and Fist

1. Find 5 small rocks.

2. Place one rock in your dominant hand and the other hand behind your back. Place the other rocks on the ground.

3. Throw the rock in the air. While it is in the air, grab one rock on the ground with the same hand and catch the rock in the air.

4. If you are successful, throw one rock in the air again until you have 5 rocks in your hand.

5. If you do not catch the rock in the air, pass the rocks to the next player and say “your turn” in Cree: “kîya” (kee uh).

6. Once you have mastered your dominant hand, play with your other hand.

Want to learn more Indigenous games? Click this link to learn more:

Active For Life – 5 Indigenous Games to Play with your Children

Lake Diefenbaker

Named by the Cree as “Kisiskatchewanisipi”, meaning “swift-flowing river”, the South Saskatchewan River is the 7th longest river in Canada. It is fed from the Old Man, Bow, and Red Deer Rivers in southern Alberta. Several hundred kilometers downstream, the South Saskatchewan River merges with the North Saskatchewan River to form the Saskatchewan River. High water levels of the South Saskatchewan River could frequently cause dangerous ice conditions downstream in Saskatoon, while in the summer months the Qu’Appelle River would frequently dry up.

Lake Diefenbaker was formed by the creation of Gardiner Dam and the Qu’Appelle Dam across the South Saskatchewan and Qu’Appelle rivers. Construction began in 1959 and the lake was filled in 1967. It is the largest body of water in southern Saskatchewan. Prior to construction of the dams, only 1% of the river’s flow in Saskatchewan was used.

Lake Diefenbaker is a reservoir measuring about 225 kilometers long with about 800 kilometers of shoreline. It has a maximum depth of 66 meters, but water levels can fluctuate 3-9 meters each year. There are hundreds of bays and coulees. The flow of the two rivers are regulated and by diverting a portion into the Qu’Appelle River, it lessened the power of the South Saskatchewan.

Water from the lake is used for municipal water supplies, irrigation, power production, and recreation. Approximately 45% of Saskatchewan’s population receives their drinking water directly or indirectly from Lake Diefenbaker. Its water is used by more than 450 farmers to irrigate their crops. The water that is released through Qu’Appelle Dam adds to the water quality and supply in the Qu’Appelle River, which meets the supply needs for Regina, Moose Jaw, and Kalium Chemical Potash Mine at Belle Plaine. Over 90% of the water released from the lake moves through the turbines of the Coteau Creek Hydroelectric Power Station to generate electricity and provide a steady water flow downstream. It provides about 19% of the hydro-electricity generated by SaskPower.

The lake is home to 26 species of fish and the sandy beaches make a habitat for the endangered Piping Plover. The area is also home to a diverse population of North America’s wildlife and waterfowl. Lake Diefenbaker’s clear blue waters are perfect for swimming, boating, kayaking, and water sports.

The lake was named after John G. Diefenbaker, former Prime Minister of Canada.

Gardiner Dam & Qu'Appelle Dam Construction

Gardiner Dam is one of the largest earth filled dams in the world and the third largest embankment dam in Canada. It measures 5000 meters long and 64 meters high. It discharges 7500 cubic meters of water per second. Qu’Appelle Dam is 27 meters high and 3300 meters long.

Gardiner Dam was named for James G. Gardiner, former Premier of Saskatchewan. It is owned and operated by the Saskatchewan Watershed Authority.

The original idea of building a dam on the South Saskatchewan River came from explorers Captain John Palliser and Professor Henry Yule Hind in the late 1850’s. A dam would allow the South Saskatchewan River to connect to the Qu’Appelle River, which would create a navigable waterway from Fort Garry to the Rockies. It took nearly 100 years for the idea to become reality.

During the “Dirty Thirties”, people longed for a water source that could be depended on. In 1944, Federal Minister of Agriculture James G. Gardiner authorized the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration to begin test drilling for a dam on the river. An agreement was made by the Federal and Provincial Governments in 1958 to construct the dam. The Saskatchewan government would contribute $25 million and the Canadian government would provide $95 million. The PFRA was responsible for planning, designing, and supervision construction of the Gardiner and Qu’Appelle Dams.

Construction brought some unique challenges. World renowned geotechnical engineering specialists were sought out for advice. They began to excavate earth fill from the land purchased from farmers and compacted along the east side of the river. Later in the year, the same was done to the west side. More than 4 miles in length, five diversion tunnels were created. A massive electrically powered machine called “The Mole” was used to bore holes 25 feet in diameter and then it would scoop up the cuttings and pass them back to be hauled away in railway mine cars. Every 40 feet, steel ring beams were installed. Construction on the intake shafts at the upstream end of the tunnels began. Their purpose was to take water from the reservoir as it filled and feed it into the tunnels. Control gates were built to regulate the flow by raising or lowering them. Five tall cone towers contain the hoists. It took 3 years to complete the tunnels, which have concrete lining 30 feet thick. “Penstock” steel liners were installed in the downstream portion of 3 of the tunnels, to supply water to the hydroelectric power station.

Construction on Qu’Appelle Dam was started in 1963, as was the spillway on the large dam. The spillway is a precautionary measure that allows water to be passed through when more water flows from the mountains than can be used. The spillway is just over a kilometer in length. In 1964, water was diverted through the tunnels. The dam was protected by 590,000 tons of rip-rap.

An official opening ceremony was held on July 21, 1967. There were several guests in attendance who played a part in the project including Dr. W.B. Tufts, President of Saskatchewan River Development Association, Right Honorable John F. Diefenbaker, Prime Minister of Canada at the start of the project, Honorable T.C. Douglas, Premier of Saskatchewan at start of the project, (both Diefenbaker and Douglas signed the original contract to start construction of the dam), Right Honorable L.B. Pearson, Prime Minister at time of completion, Honorable Ross Thatcher, Premier of Saskatchewan at time of completion, and Ron McLelland, Federal Member of Parliament for the area around the dam. C.O. Cooper, who was Federal Member for the area during the first years of construction had passed away before the opening of the dam.

South Saskatchewan River Water Levels

Lake Diefenbaker Tourism

Bonnie View Church

The Bonnie View Church congregation was formed in 1905. As several denominations would worship there, it was called a Union Church, under auspices of Presbyterian Mission. Church services were initially conducted by Mr. & Mrs. Potts in their home. Students would come to the area during the summer months to service the congregation.

After the Bonnie View School was built in 1907, church services moved from the Potts home to the school. The first ordained minister to serve was Rev. R.A. Hanley from 1908-1909. The church congregation was known for their outstanding choirs.

Rev. L.A. Muttit served from 1924-1932. He has the record for length of service on this field. The school became very crowded during this time for the size of the congregation. There were discussions about putting an addition onto the school. Peter Coutts suggested building a church, and was supported by Rev. Muttit. It was voted on and they decided to canvass for construction. People donated money as well as their time to help with construction. It was entirely built by local labour and entirely funded by congregation members without use of church funds.

In 1928, the new Bonnie View United Church was opened, free of debt. The exterior of the church was made from Estevan red brick. It has Gothic Revival influences with its crenulated bell tower, framing towers with battlements, and pointed arch windows. The interior has hardwood floors, wood trim, and an arched ceiling. The beautiful structure sits on a hill overlooking the South Saskatchewan River Valley, just south of where the school was located.

It held regular services and Sunday school lessons, as well as hosted many weddings, baptisms, funerals, and Christmas concerts. During its busier times, up to 38 children attended Sunday school weekly. Many social events and fowl suppers were also held in the church. The 1930’s hit hard, as they did for many on the prairies, but the church fire was always lit, the floors were swept, the snow was shoveled, and the handyman donated his time.

In 1958, there was a trend towards larger farms and fewer residents. Bonnie View Church was attended and supported by only a few families. The decision was made to close the church. It was reopened briefly during the construction of Gardiner Dam during the 1960’s. Dam construction workers and their families would attend Sunday services. They were drawn in by its view. After dam construction was completed, furnishings were gradually sold to other congregations, and only the bare walls remained.

In October 2000, Bonnie View Church was designated as a Saskatchewan Heritage Site.

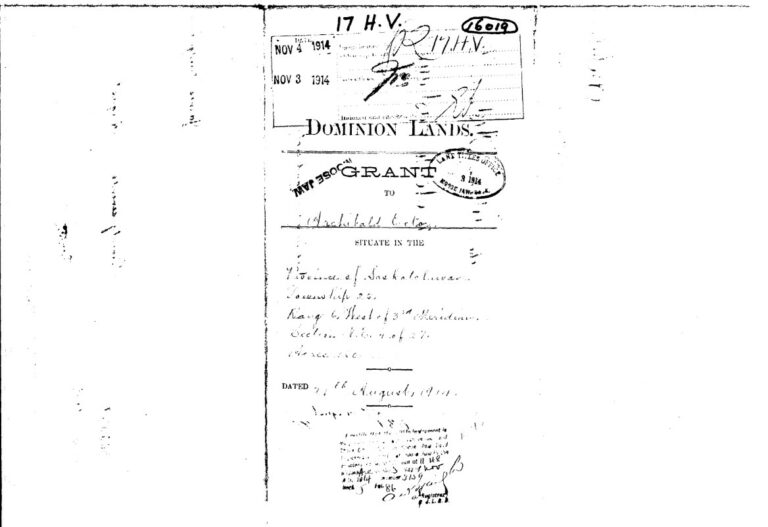

Early Settlement to the Area & Ector Homestead

Early Settlement

Henry Kelsey was believed to be the first explorer to reach present day Saskatchewan around 1690. He was an English fur trader and explorer employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company. His exploration into the interior of Western Canada opened up new trade routes and laid the groundwork for further expansion and settlement. Anthony Henday was also an English explorer employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company who partook in expeditions into present day Saskatchewan in the 1750s and played a key role in establishing trade relations between the HBC and Indigenous groups, particularly the Cree and Assiniboine. Peter Fidler was a British-Canadian surveyor, cartographer, and fur trader who played a significant role in exploring and mapping western Canada in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He mapped the Saskatchewan River, explored the Cypress Hills area, and established fur trading posts and settlements. His interactions with Indigenous communities helped to establish trade relationships and alliances. David Thompson was known for his extensive explorations of western North America in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He explored the Saskatchewan River and established fur trading posts in the area. Captain John Palliser led the Palliser Expedition, commissioned by the British government between 1857 and 1860, to survey and assess the western Canada, particularly between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains. His team of naturalists, geologists, botanists, artists, and Indigenous guides mapped rivers, lakes, mountains, and plains, collected geological and botanical specimens, and documented Indigenous cultures and territories. Professor Henry Yule Hind was a geologist, explorer and educator and was part of Palliser’s expedition in 1857. He conducted geological surveys and assessments of the natural resources and potential for agriculture and settlement. He had the initial idea of connecting the South Saskatchewan and Qu’Appelle Rivers, which would come to fruition a hundred years later in the form of Gardiner and Qu’Appelle Dams.

In 1871, the Canadian government entered into Treaty 1 and Treaty 2 to secure consent from Indigenous nations of those lands for immigrant settlement and for development of natural resources.

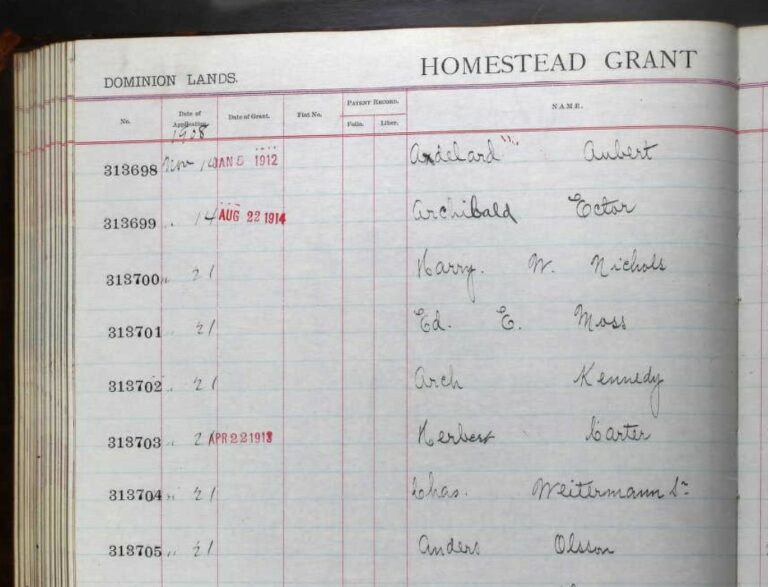

The Dominion Lands Act 1872 created free homesteads of 160 acres for settlers from land previously inhabited by Indigenous peoples. The lands in Western Canada could be granted to individuals, colonization companies, Hudson’s Bay Company, railway construction, municipalities, and religious groups. Land was set aside for First Nations reserve and in 1883 an amendment was made to also set aside land for what are now National Parks. Metis lands were organized outside of the Dominion Lands Act. The North West Mounted Police were established in 1873 to guarantee safety of the settlers. The Department of the Interior helped to “attract economic immigrants, established a minister responsible for Indian affairs, and to control and manage the lands and property of the Indians in Canada”. Transcontinental railroad construction allowed for expanding European settlement to the prairies.

The homestead policies of the Dominion Lands Act created eligibility requirements, a list of settler responsibilities, and a standard measure for surveying and subdividing land. The land was surveyed and subdivided by the Department of Interior’s Dominion Land Survey. Over 1.25 million homesteads were created over 80 million hectares, creating the largest survey grid in the world. The land was divided into townships. Each township comprised 36 sections of 260 ha, which were broken into 65 ha quarter sections. Even numbered quarter sections were homestead lands, odd numbered sections were sold for pittance to the Hudson’s Bay Company, CPR, CNR, Henderson Land Company, and Saskatchewan Vally Land Company. These companies then sold the land to settlers who had not homesteaded or wanted to acquire more land. The surveyed land was marked by metal pins and townships were marked by metal stakes topped with plaques.

Between 1870 and 1930, roughly 625,000 land patents were issued to homesteaders. In 1930, the Dominion Lands Act was repealed and the lands and resources were transferred from the federal government to the provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Alberta.

The policies evolved over time. Before 1874, any man over the age of 21 was eligible for a quarter section. In 1874, the age dropped to 18 to allow younger families to homestead. In 1876, women over 18 were eligible if they were the sole head of the family. In 1919, widows of war veterans became eligible.

The government settlement plan stated that you could get a free homestead if you paid a $10 administration fee for a quarter section of 160 acres. You would have to build a habitable dwelling and live there for 6 months of the year for 3 years. Depending on the year you applied, you would also have to break ground and prepare a certain amount of crop each year. These homestead requirements helped to discourage those purchasing as speculation properties, to sell later for profit, and encouraged long term agricultural settlement. Once the authorities decided that you had “proved up” the homestead, the settler received ownership of the land. If no improvements were made, then the land could be taken back by the government and sold to other settlers. The Homesteaders Act of 1882 also stated that once you have completed the homestead duties, you could buy another quarter section for $3/acre by pre-emption. This land could be purchased up to 3 years after the homestead was patented and could remain unimproved for 6 years after date of entry.

In 1915, as a result of The Great War, an amendment was made allowing residence and cultivation duties to be waved for those whose injuries during service in the war made compliance with the duties impossible. The Soldier Settlement Act of 1919 enabled returning soldiers to settle in any part of Canada where “conditions with soil, climate, social development and transportation provided suitable openings.”

Sunset Beach is located in what is now the RM of Loreburn, but was in the early 1900’s known as the Bonnie View District. It is said that the Bonnie View District was named by Mrs. G.H. Potts who said as she looked west to the hills beyond the river “Well, isn’t that a bonny view?”

William Zettel and Henry Doege were the first in the Bonnie View area in 1903. They homesteaded adjacent quarters in section 10, building a sod house on one quarter and a sod barn on the other. Once they proved up their claims, they bought more land by pre-emption.

In the early 1900’s, settlers to the area often came by train as far as Davidson and then it was about a day’s trip to what is now the Loreburn area. People would often travel back to Davidson once or twice a week for supplies. Around 1908, the train came through the Loreburn area, allowing for shorter trips to Elbow for supplies instead of Davidson. Small stores, post offices, livery stables, and lumber yards provided much needed supplies.

Trees by the river were chopped down to use for firewood and to make frame houses. Sod houses were also common. To get around, horses and wagons or sleighs were used. Oxen and horses were used to plow the dirt. Oil lanterns were used for lighting. In the winter, snow was melted for cleaning, bathing, and laundry.

While current farmers in the area still have to deal with unpredictable weather conditions and pests, they were all new situations to the settlers. The cold winters sometimes brought early frost which damaged crops and gardens if you weren’t prepared for them. Blizzards could come up very quickly and with very little landmarks, it made getting from one place to another very difficult if you got caught in a snowstorm. Luckily, horses often seemed to find their own way back home. Sometimes a line was strung from the house to the barn so you could follow it to feed the stock during a snowstorm. Lightning strikes were common and could cause devastating prairie fires. Many homes and barns were lost due to fast spreading fires. Hailstorms were also known to flatten crops and damage homes. The drought and dust storms of the “dirty thirties” brought all kinds of problems. Many families abandoned their homesteads and headed north, further west, or back east. (It is estimated that over 247,000 people left the prairies in the 1930s.) Those lucky enough to get a crop had to deal with the grasshoppers and gophers. Another pest that people encountered on the prairies were the mosquitos. There were also reports of cyclones and tornados in the area, and even an earthquake around 1907 or 1908!

Weather wasn’t the only thing they had to deal with. Most had left behind family and friends to venture to a new, unknown land. Illnesses such as typhoid fever, double pneumonia, blood poisoning, and the 1918 flu epidemic affected settlers. There were limited medical professionals in the area and they had to travel far distances in all weather conditions. Dr. Monkman and Nurse Weir serviced the area for many years, travelling long distances to homesteads over a 50 mile span to assist with births and illnesses. Infant deaths, farming accidents, and freezing to death were unfortunately common occurrences. 1914 also brought The Great War, so there were many settlers who set off to other parts of Canada or overseas in the army or RCAF. Some who returned were never the same, and others never returned at all.

Life wasn’t all hardships. They learned to rely on neighbors and friends, and gatherings were common. Over time, sports such as broomball, hockey, skating, curling, shinny, and baseball became popular past times. The church and schools would have dances and concerts.

The local flora and fauna provided sources of food. Wild ducks, prairie chickens, partridge, deer, antelope, and rabbits were all found in the area. The river was a great source for fish year-round. Saskatoon berries, chokecherries, buffalo berries, wild strawberries, and mushrooms all grew in the area. Potatoes and vegetables were planted. Poplar and willow trees provided wood for fuel. Russian thistle, crocuses and wild flowers also covered the area. During the drought years, relief trains from Ontario brought apples and pears along with other supplies.

Eventually, the area grew as automobiles and electricity made life a little bit easier. The communities continued to grow as more and more settled in the area. Several small villages and towns were created surrounding the river.

Ector Family Homestead 27-25-6 W3

Archibald Ector left his hilly, stony farm in Ontario and made his first trip to Saskatchewan in 1906. He was drawn to the prairies as a land of opportunities. In Saskatchewan, he threshed with Wellington Dormer in Arcola. He returned again in 1907. In 1908, he took the first train from Moose Jaw to Outlook (note: Elsie’s story states Moose Jaw to Outlook, Marjory’s story states Moose Jaw to Elbow). He then ventured out to take up homestead on NE 27-25-6 W3, which is the current location of Sunset Beach.

In order to prove claim, he was required to return in 1909 and 1910 and to reside and break ground on the homestead. He built a shack to live in on the homestead. He left his wife, Emmaline, and 9 kids to manage the farm in Ontario until he had proved his claim.

In 1911, he sent his settler’s effects with his eldest son William (Willie), and brought his wife and 7 kids by train to Elbow, where they were met by James Campbell’s sleigh team and taken to the Ellison farm, a common stop for travellers in the area.

Archibald built a large 2 story house with 4 bedrooms, “like the one they left in Ontario”. The family moved in before the house was completed. In addition to the house, they also constructed a barn made of poles covered with straw, which was very warm, but also very dark. A new barn was built in 1916 with a track and slings in the loft. A sod henhouse was built into the side of a hill. They had a well by the river and had to carry pails of water back to the house.

In 1916, a cyclone went through the property, which flattened crops and flooded the chicken coop. They lost several chicks, but were thankful that the barn was undamaged.

The children attended Bonnie View School during the summers, getting rides in a horse drawn buggy when available, or walking the 3.5 miles to school when the horse was needed elsewhere. In 1917, the family purchased their first car.

In 1919, Archibald purchased 5 quarters of land 2.5 miles north of Elbow and moved the family closer to town. His eldest son, Willie took over the homestead farm. In 1921, Willie returned to Ontario where he married Bessie Atkinson and they returned to live on the family farm. Willie and Bessie raised a family of 5, all born at home- Marjory, Robena, Wilma, Myrtle, and Archibald (Archie). Willie’s children attended Wild Lily School, 2.5 miles from home. Marjory, as the oldest, would drive the horse and buggy or sleigh to school and stabled the horse in the school barn.

A large shelter belt was planted as well as many fruit trees (plums, cherries, raspberries). There were also chokecherries, saskatoon berries, and pin cherries in the ravine that were picked and canned. A garden was grown with beautiful flowers and shrubs. Veggies were canned.

The farm was worked with horses, a plow, cultivator, seed drill, harrows, and a binder to cut the crop. It was stooked and threshed later. They raised horses, cattle, and chickens, and even some pigs for a few years. Wood was cut from the pasture to heat the house. Coal oil lamps were used for light. They milked the cows, made butter, made laundry soap from fat and tallow, and sold eggs. Meat was cured or canned. Clothes were hand washed on a washboard. Sewing, knitting, hook rugs, braiding, crocheting, and embroidering were all well used skills. Most clothes were sewn, while socks, mitts, toques, and scarves were knit. Beautiful quilts were made. Willie was a mechanic and did blacksmith work.

Many other families packed up and headed north, west or back east during the “Dirty Thirties” when drought plagued the prairies, but the Ectors decided that “we must hold on”. At times, dust storms could suddenly turn everything to complete darkness. Wind was used to keep a 6 volt battery charged so that a few electric lights could be used.

Outside of chores, the children occupied their time by roaming the ravines, building playhouses, fishing on the river, and picking berries. Skating, hockey games, sleigh rides and dog sleds were fun winter activities. Books and magazines were popular ways to pass time, as was listening to the radio or attending school dances.

Their first tractor was bought in the 1930s. Eventually, stooking and threshing were replaced by swathers and combines. They always kept a team of chore horses.

All four daughters married and moved to other farms. Archie stayed and helped out on the farm. In 1954, Willie, Bessie and Archie went to Ontario for a holiday and when they were leaving to return home, they were in an accident that seriously injured Bessie. After a few months, she was moved to Moose Jaw Hospital. Willie died that October and Archie took over the farm.

In 1957, Archie returned to Ontario and married Shirley Cook. They returned to the family farm where their three children were born- Doug, Steven, and Marilyn. They were the fourth generation of Ectors to reside at the farm. Electrification came to the rural areas during this time, so lighting and electric appliances were a welcome addition to the farm.

In 1961, the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA) bought Archie’s farm in preparation for the South Saskatchewan River Project. Archie and family purchased another farm. Their barn was torn down and other buildings were moved or sold at auction in 1963. The old farmhouse that Archibald built was bought by Shirley’s parents and moved into Elbow. Brush cutters cleared the trees from the ravines.

Some of the Ector family descendants are Sunset Beach lot owners.

“I often think of the beautiful scenery in the spring by the river, blossoms by our orchard and the sweet scent of the trees in the valley, all in bloom. In the fall, one could stand and look at the magnificent array of autumn colors all the way to the river. Such a picture!” -Elsie Ector Baker

(Information gathered from submissions of Elsie Ector Baker (Archibald’s daughter) and Marjory Ector Pederson (William’s daughter) to “From Mouldboard to Metric- A History of Loreburn & District”, and personal communication from MaryAnne Depper (William’s granddaughter))

We would like to thank Lacey Weekes, Jeff Cappo, Wyatt Brown, and Carmen Heinrichs for their content contributions to this project.

This Interpretive Trail Sign Project was funded in part by grants from Trans Canada Trail, Saskatchewan Trails Association, and the Truth and Reconciliation Fund at the South Saskatchewan Community Foundation.

Thank you to Dakota Dunes Community Development Corporation for sponsoring the Interpretive Trail Grand Opening Event and BBQ.